Single News

New study on the history of Weleda published

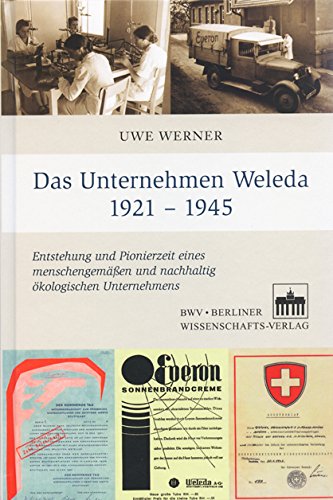

A new study on the history of Weleda AG has been published by the Berliner Wissenschaftsverlag which for the first time gives a thorough insight into the fate of the company in the 1930s and 1940s using documents from the archives. The author is the historian Uwe Werner. NNA correspondent Wolfgang G. Voegele took a look at it.

BERLIN (NNA) – Werner is a former archivist at the Goetheanum and author of the standard work on anthroposophists in National Socialism, Anthroposophen im Nationalsozialismus (1999). His notable work on the history of Weleda AG is a continuation of the documentation about Rudolf Steiner and the establishment of Weleda published in 1997, “Rudolf Steiner und die Gründung der Weleda” (Beiträge zur Rudolf Steiner Gesamtausgabe, Issue 118/119), which concludes with Steiner’s death in 1925.

The ban on anthroposophy during the Nazi period meant that Weleda in Germany (Schwäbisch Gmünd) was also faced with a threat to its existence. Werner explains how the company nevertheless managed to survive the Nazi regime and the war years relatively unscathed. On the one hand this was because it was the branch of a Swiss company and on the other hand because of its specifically anthroposophical foundations: these extended as far as the social structure of the company and formed a spiritual counterweight to fascism in Europe.

As a result its staff had the strength for passive resistance which deliberately subverted or circumvented the measures of the regime, Werner argues. The author also deals with the threat faced by Weleda AG from tendencies in the Nazi regime to want to take it over.

The book is divided into three parts dealing with the establishment of Weleda (1919 to 1924), the pioneer phase of an “anthroposophically-oriented company” (1925 to 1932) and survival in an inhuman environment (1933-1945).

The early years

The chemist Oskar Schmiedel, who had a doctorate in chemistry, had founded a laboratory in Munich with the painter Imme von Eckardstein as early as 1912 which manufactured plant paints according to indications from Rudolf Steiner. Soon a start was also made on the production of cosmetic products and performing analyses for doctors. In 1914 Schmiedel moved to Dornach where he made paints and protective varnishes for the Goetheanum building but also medicines for those doctors working with anthroposophy. After the First World War a research laboratory was also established in Stuttgart (as part of the “Komtag“ association).

Steiner’s fundamental socio-political ideas as they emerged in 1919 in the threefolding movement also became of relevance for the future Weleda in that associative elements, such as proposed by Steiner in the macro-social and economic field, also influenced the collaboration with doctors and patients. In 1921 the “Futurum-Laboratorium” (subsquently Weleda AG) was established in Arlesheim.

In 1924 the facilities in Germany were incorporated as a branch of the Swiss parent company, something which also has to be seen against the background that after the Hitler-Ludendorff Putsch of 1923 Rudolf Steiner judged the political situation in Germany to be very uncertain. The survival of the company in Germany was in part due to this structure.

Anthroposophically motivated corporate culture

The book pays tribute to the work of the leading people in positions of responsibility (incl. Oskar Schmiedel, Emil Leinhas, Edgar Dürler, Fritz Götte, Wilhelm Pelikan, Wilhelm Spiess, Joseph van Leer). Werner further throws light on the naming of the company, describes the first stock of medicines and reproduces illustrations of written notes by Steiner for recipes and his sketches for product advertising.

There is also a description of the introduction of voluntary rhythmical gymnastics and hygienic eurythmy (1927) and the “works periods” as part of an anthroposophically motivated corporate culture. These periods allowed staff to obtain an understanding of all company processes from production to marketing. The origin of the Weleda-Nachrichten and the relationship with the health insurance funds is also discussed, as is the way that turnover developed.

Particular attention is paid to the year 1935: as part of the ban of the Anthroposophical Society in Germany, Weleda staff were also denounced and interrogated by the police. Werner includes a police report. In 1938/40 the existence of the company hung in the balance; in 1941 it was ordered to close and a “wartime emergency programme” entered into force. Ultimately, the fact that the parent company of the firm was based in Arlesheim in neutral Switzerland helped not just with regard to the Nazis but also the Allied occupation forces.

Fascinating contribution

Fritz Götte, who became the director of Weleda in 1941, warned in 1976 against a growing bureaucratic concentration of power in the EU. This had to be countered by forces of direct democracy, such as a “grassroots movement for unrestricted healthcare”. Today such counter movements are alive in patient organisations and other civil society movements as well as NGO interest groups.

An appendix contains hitherto unpublished documents, including a list of doctors from February 1942 attesting to the report on Weleda’s pharmaceutical preparations for the Reich Health Authority in Berlin. It contains the name of more than 130 doctors, municipal and private hospitals, sanatoriums, etc. The many illustrations, some of them in colour, are also impressive. An index of names and a subject index make it easier to find one’s way around. All in all, Werner’s book is a fascinating contribution to the history of the anthroposophical movement.

Uwe Werner: Das Unternehmen Weleda 1921-1945. Entstehung und Pionierzeit eines menschengemäßen und nachhaltig ökologischen Unternehmens. Berliner Wissenschaftsverlag, Berlin 2014. 260 pages, €24.80.

END/nna/wgv/cva

Item: 141214-02EN Date: 14 December 2014

Copyright 2014 News Network Anthroposophy Limited. All rights reserved.