Single News

Rudolf Steiner – the sensation of his day

REVIEW | Rudolf Steiner’s „blockbuster“ lecture tours in 1922 have been documented for the first time in Archivmagazin, including the attack on him by Nazis in Munich. NNA correspondent Wolfgang Vögele couldn’t stop reading.

DORNACH (NNA) – In the early 1920s, an occult wave was rolling across Germany, mediumship and astrology were booming. Today we would talk about an esoteric boom. The silent films also benefited from this situation and attracted people into the cinemas with shady characters from mystery and crime: „The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari“ or „Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler“. At the same time another name also electrified audiences: “Dr Rudolf Steiner”. People streamed to his lectures because they considered him to be some sort of magician or clairvoyant.

His popularity was also reflected in the satire of the time: the magazine Simplicissimus published a whole-page drawing in which snobbish ladies and gentlemen in a Berlin salon were discussing the latest fashion and developments in science and on the cultural scene: “Picasso is said to have moved on from Cubism.” – “Einstein is sticking to his formula.” – “By the way, did you go and see Rudolf Steiner?”

The famous concert agency Wolff & Sachs, which had applied to organise two lecture tours by Steiner through several German cities, had good reason to be satisfied. On the first tour alone, in January 1922, Steiner spoke in front of about twenty thousand people. But this roll ended unexpectedly when during the second tour in May militant opponents from nationalistic populist (voelkisch) circles organised trouble in Munich and Elberfeld so that Steiner decided against a third tour.

What had happened? In Munich, Steiner had been “physically threatened and put in danger of his life by hooligans at the instigation of a newspaper,” as Friedrich Rittelmeyer wrote in Rudolf Steiner Enters My Life. Had the conspirators really planned to remove Steiner in an assassination attempt? Or was this a myth set up by anthroposophists, as the American historian Peter Staudenmeier believes?

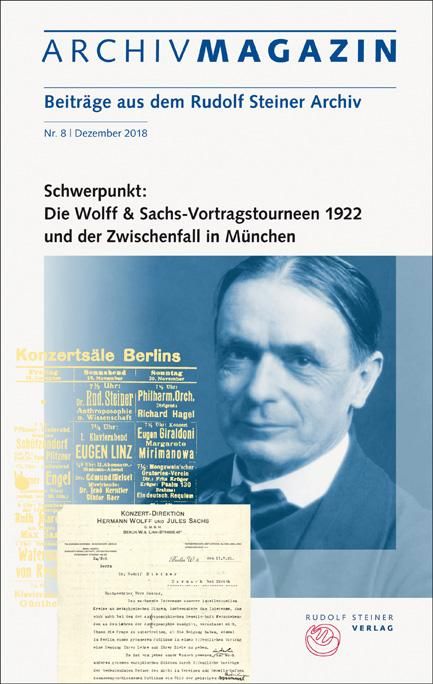

A unique documentation

Anyone who takes a look at the most recent Archivmagzin (No. 8) from the Rudolf Steiner Archive will be able to find the answer. A large part of the magazine is taken up with a comprehensive documentation of the two Wolff & Sachs lecture tours in 1922, the first time this has been done, in which Steiner was the focus of German public opinion as never before.

How has it come about that he was generally seen by his time as being on the left of the political spectrum whereas today some critics present him as a German nationalist or nationalistic racist? Even during his lifetime Steiner experienced the contradictory effect of his words: “Beyond the border I am a Pan-German, within Germany I am an enemy, a traitor to German culture among the Pan-Germans and those who think like them,” as he put it in a public lecture in Stuttgart on 25 May 1921.

The editor Anne-Kathrin Weise draws on documents in the Dornach archives, including eye-witness reports and letters, many of which have been published for the first time.

A lengthy introduction to the period shows that democracy in the young Weimar Republic was by no means secure. Right-wing terrorist organisations tried to assassinate leading politicians. Growing inflation brought about a feeling of insecurity among broad sections of the population.

The practical solutions promoted by anthroposophy in various fields of knowledge and life, primarily the movement for the threefold order of the social organism, made it a target for nationalistic and antisemitic forces. They saw Steiner as a stooge of the victorious powers and the agent of a global Jewish and Masonic conspiracy. Hitler’s mentor, Dietrich Eckart, had published a long article about Steiner in 1919 in which he mocked Steiner’s social impulse as “threefolding puppet”. Hitler himself decidedly rejected threefolding as early as 1920. According to police intelligence reports, when after his speech at the Munich Hofbräuhaus on 11 May 1920 one person recommended the threefolding idea as a possible solution to the social question, Hitler replied: “We don’t want any new ideas but to defend the old ones which have been seen to be correct.”

The reaction of nationalistic populist (voelkisch) groups to Rudolf Steiner is set out in detail. This is followed by chapters on the progress of the tour, the correspondence, business documents, an index of the papers relating to the Wolff & Sachs tours in the Rudolf Steiner Archive, a list of press reports, press reports and reminiscences of eye-witnesses. All texts have been provided with explanatory notes.

Dramatic events

The dramatic occurence, which took place on the evening of 15 May 1922 in Munich’s premier hotel “Vier Jahreszeiten”, was even reported as a “riot” in the New York Times. The headline says: “RIOT AT MUNIC LECTURE. Reactionaries Storm Platform When Steiner Discusses Theosophy”.

It becomes clear from eye-witness reports that many people decided specifically as a result of the lectures on this tour to engage more deeply with anthroposophy.

“Thus Heinrich Liedvogel wrote how grateful he was that his father had taken him along to the lecture as a recalcitrant eighteen-year-old and that Rudolf Steiner had at the time made an ‘indelible impression’ on him which stayed with him for the rest of his life. He was impressed how Rudolf Steiner silenced the hecklers which were, however, subsequently to seize power. Fifteen year later (1933) he experienced in the same hall how the ‘clique of those earlier hecklers’ had ‘grown into a dragon which had, at least outwardly, destroyed the intellectual life of Germany’.” (p. 48)

Hans Büchenbacher, who in Munich had become aware at an early stage that Steiner was on a death list and that an attack was planned, organised his own protection force since the police had refused to take the appropriate measures.

Steiner, too, aware of the threat to his life, had asked Büchenbacher whether he should give the lecture at all. “It will probably reach the point that I can only speak any longer in the occupied Rhineland.” (The Rhineland was occupied by the Allies from 1918 to 1930.)

All the memoires agree in their description that after the lecture, while the audience was still applauding, attackers stormed the platform as the speaker was just about to leave the hall. He only just succeeded in closing the door behind him. Meanwhile the anthroposophists pushed the attackers down from the platform. There followed a scuffle, other reports refer to a general brawl. The attackers had worn swastikas. They were equipped with sticks, knives and firearms. The push back had already been practised in the hall in the morning. That the descriptions of the anthroposophists were not exaggerated is backed up by newspaper reports from Munich which document the brutal actions of the Nazis against individuals and events by dissenters.

Shortly before the incident, the Munich weekly Heimatland (edited by the subsequent editor-in-chief of the Völkische Beobachter, the organ of the Nazi Party) wrote: “Are there no longer any men in Munich who feel themselves to be German and who will prevent the arrival of such a scoundrel? Above all, will our battle-hardened youth with its patriotic ethos tolerate this provocation? If ever there is a target worthy of rotten eggs and apples, there is none more worthy for this kind of projectile of contempt than the anthroposophical Cagliostro and betrayer of the homeland.”

For the Nazis, Steiner was a parasitic “enemy of the people”. The Völkische Beobachter wrote: “Our pencil bristles at seriously engaging with such a charlatan and enemy of the German people. He has millions at his disposal to pollute our nation with his teachings and through his influence on the widest circles he has turned into a danger to our present and our future.” (p. 211).

Steiner’s Dornach collaborator Edith Maryon, who had been worried about Steiner beforehand already, received a telegram: “Survived Munich. Steiner”.

Conclusion

This documentation makes clear once again the incompatibility of anthroposophy and nationalistic racist thinking. There will be few people today inclined to present Steiner as a martyr. Yet many details have to be overlooked to reach the opinion that the Munich incident was a harmless interruption by some boisterous students. Steiner, against whom the press had agitated beforehand, was in danger of being beaten up and, if possible, “eliminated”. That this did not happen is due to the clever defensive measures of the anthroposophists.

The extraordinary courage with which Steiner exposed himself to the ever more brutal actions of his opponents to present his ideas must be admired. He finished the tours, which he admitted exhausted him, with unshakeable equanimity and his familiar self-discipline.

The tour lectures

New edition in the Steiner complete works (GA – Gesamtausgabe), volume 80a

Anne-Kathrin Weise also edited the lectures given on the tours which have now been published as GA 80a in the complete works. They form an extraordinary bundle within Steiner’s public lectures. They are individual lectures – the speaker was only able to present briefly things he set out in greater detail in lecture cycles – yet they have the appeal of precision. They are an introduction to the nature of his worldview from the mature perspective of the 60-year-old.

It is not evident from the tone of the lectures that they were held in a sometimes tense atmosphere. A large part of the audience appears willing to follow the speaker in his for them unusual and demanding lines of thought. The great applause, which even the newspaper reporters experienced as being unusual, certainly did not come just from anthroposophists since they only formed an insignificant minority among the more than thousand people in the audience on each occasion.

In almost every lecture Steiner fought against misunderstandings and the caricatures of his teachings. He differentiated his epistemological method sharply from experimental parapsychology, eastern yoga, and emotive mysticism and kept attempting to make the scientific nature of his research method clear from ever new perspectives. He also referred to the way in which anthroposophy could be productive in education, medicine, the religious life, etc.

The lectures give an insight into what an introduction to the nature of anthroposophy looked like almost 100 years ago. The notes explain the location and audience numbers. Entries from Steiner’s notebooks, press reviews and two recollections of the incident in Munich are included.

END/nna/wgv/cva

ARCHIVMAGAZIN. Beiträge aus dem Rudolf Steiner Archiv: Nr. 8/2018, Wolff & Sachs-Vortragstourneen 1922 und der Zwischenfall in München. Rudolf Steiner Verlag, Basel 2018 (285 pages, illustrations), €24.80.

Rudolf Steiner: Das Wesen der Anthroposophie. Dreizehn von der Konzertagentur Wolff & Sachs organisierte öffentliche Vorträge, gehalten in Berlin, München, Stuttgart, Frankfurt am Main, Mannheim, Köln, Elberfeld und Breslau zwischen dem 19. November 1921 und dem 18. Mai 1922, Rudolf Steiner Verlag, Basel 2019 (625 pages, illustrations), €68.00.